As Gosu programmers we’ve been using functional programming now for several years. Finally Java 8 brings its own style of functional programming with a combination of new features: Lambda expressions and Functional interfaces. We introduced these concepts in What’s New with Gosu’s Java 8 Support. If you haven’t already read that article, it’s probably better to before continuing with this one; concepts and features explained there are assumed to be understood in this article. Here I’ll cover a little more on the subject, and focus more on the benefits of Gosu’s function types. Then I’ll show how a generic structure type can be more suitable in some situations than a function type. Finally I’ll introduce a cool new feature that adds extra type-safety to Gosu generics without compromising usability.

Because Java lacks function types it provides a bunch of functional interfaces to bridge purely structural lambda types with its purely nominal type system. For example, Function<T, R> is the functional interface for a lambda used in Stream#map():

public interface Function<T, R> {

R apply(T t);

...

}

public interface Stream<T> extends BaseStream<T, Stream<T>> {

<R> Stream<R> map(Function<? super T, ? extends R> mapper);

...

}

In Java you use map to apply a function to each value in a stream, which usually corresponds with values in a Collection:

List<Point> points = getPoints();

List<Integer> xCoords = points.stream().map( pt -> pt.x ).collect( Collectors.toList() );

Using the same method in Gosu we have:

var points = Points

var xCoords = points.stream().map( \pt -> pt.x ).collect( Collectors.toList() )

But if we were to design a map() method in Gosu, we wouldn’t need a Functional interface. Instead we’d use a Function Type via block syntax:

function map<R>( mapper(T): R ): Stream<R>

And because Gosu has Enhancement types we wouldn’t need a Stream class for non-parallel uasge of map. We’d create an enhancement for all Iterable things, call it CoreIterableEnhancement, and put it in there:

function map<Q>( mapper(T): Q ): List<Q>

And we’d call it like this:

var points = Points

var xCoords = points.map( \pt -> pt.x )

Which is exactly what we do in reality. A bit more down-to-earth, no?

Let’s take a step back and compare Java’s Functional interface-based map() with Gosu’s Function type-based version:

<R> Stream<R> map(Function<? super T, ? extends R> mapper);

function map<R>( mapper(T): R ): Stream<R>

Notice the wildcard types in Java’s map. Why does Java need them here? How does Gosu get away with not having them?

These are fun questions to answer. But first, an even funner question. Why does Java need wildcards at all? The simple answer is Java’s designers chose to keep generic type variables invariant in the declaration and implement variance only at the use-site where type variable values are assigned. In case you’re not familiar with the terminology, variance determines assignability between instances of a generic type. For instance, given generic type Foo<T>:

// if T is *covariant* we can do this:

var foo: Foo<Object> = new Foo<String>() // because String is a sub-type of Object

// if T is *contravariant* we can do this:

var foo: Foo<String> = new Foo<Object>() // because Object is a super-type of String

// if T is *invariant* we can *only* do this:

var foo: Foo<String> = new Foo<String>() // because String cannot vary

Variance can be assigned in two places:

class Foo<covariant T> { ... }. This is referred to as declaration-site variance.Foo<? extends CharSequence> foo. This is referred to as use-site variance (aka wildcards).Wildcards are Java’s solution to variance. Consequently, Function<T, R> can’t declare its intended variance in its declaration, a programmer must declare its variance everywhere he uses it. Every. Single. Time. That’s what is going on with map(). The Function interface’s design is such that T is effectively contravariant and R covariant. Basically a covariant type variable represents a type that is produced by an interface, typically a method return type. A contravariant type is consumed by an interface, generally these are passed into the interface via method parameters. Thus, given its functional method, apply(), the Function interface would, if it could, declare T as contravariant and R as covariant:

public interface Function</*contravariant*/ T, /*covariant*/ R> {

R apply(T t);

...

}

T is a parameter in apply(), which is consumed by the function, therefore it is contravariant. As a return type R is covariant because it is produced from the function. But since Java generics doesn’t support declaration-site variance, the onus is on users of Function, as is the case with map():

<R> Stream<R> map(Function<? super T, ? extends R> mapper) // wildcards enforce T as contravariant and R as covariant

As Gosu users of Function what does this mean to us? Remember the Function interface, like most Functional Interfaces, exists as a bridge to Java lambda expressions. Since a Java lambda has no type of its own, its type is always inferred from a Functional Interface in context. But Gosu blocks have Function types and don’t need Functional Interfaces at all, therefore Gosu doesn’t care so much about the wildcards declared with map’s Function argument. Instead Gosu looks directly at the map() function wrapped inside of Function and verifies block expressions against that. This simply means we can pass a block expression to map() that has a parameter assignable from T and return type assignable to R:

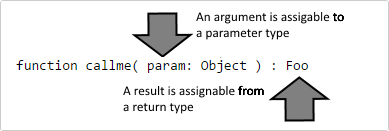

From first principles this makes perfect sense. When we call a function we pass arguments assignable to it’s parameter types and receive the result in a variable assignable from its return type. These relationships are reversed from the perspective of the function, therefore parameters are naturally contravariant and return types are naturally covariant. The takeaway from all this is that structural assignability inherent with function types naturally facilitates generic variance; all the wildcard and Functional Interface rube goldbergery is totally unnecessary and, in fact, is completely bypassed in terms of Gosu type checking with block expressions.

As we’ve just covered Gosu blocks are properly typed with function types, as a consequence there is no need for explicit variance declarations inside them. Revisiting Gosu’s map() function:

function map<Q>( mapper(T): Q ) : List<Q>

The type system ensures a block expression passed to map() is structurally assignable to function type, mapper(T): Q, saving Gosu programmers from the entire generic variance mess. In fact, since type variables in Gosu generics are implicitly covariant by default and given contravariance is predominantly used to establish structural assignment in functional types, Gosu’s function types alone solve most of the variance problem. A quick search in Java’s runtime library source supports this theory; most <? super X> usage deal with functional types or, more generally, functional relationships.

There are cases, however, where function types are insufficient. For example, take Java’s Comparable interface. It’s a functional interface that’s been around forever:

public interface Comparable<T> {

public int compareTo( T o );

}

But Comparable isn’t designed to be a functional interface per se. Meaning it’s not designed as a go-between for lambda usage. Instead, it’s designed to be implemented by more complex classes, classes that have state that can be compared such as String or Integer and so forth. So, although Comparable is technically a functional interface, a Gosu function type is unsuitable as a substitution for it – you can’t implement a function type that way. For instance, the following function type models Comparable’s compareTo() function:

block(T): int

But representing Comparable as a function type is nonsensical as Collections#sort() demonstrates

public static <T extends Comparable<? super T>> void sort( List<T> list ) {

list.sort( null );

}

Essentially this method is saying, give me a List of anything Comparable with itself or super types. Well, if we attempt to write this function in Gosu with a function type, we have this:

static function sort<T>( list: List<block(T): int> ) {

list.sort( null )

}

This is problematic in several ways. First, it’s practically unusable. For instance, we can’t call it as intended:

var list = {"forever", "alone"}

sort( list ) // error: type mismatch

We can’t pass a List<String> to this function because String is not assignable to block(T):int. Although it could be considered assignable because String does have a method, compareTo(), that satisfies the structure of the block, Gosu’s type system isn’t that lenient. Basically, since String is not a functional interface it’s not assignable to the block. And we really wouldn’t want to relax the type system to support this behavior because there could be several methods matching a given block’s structure. Indeed, String has a couple of methods that match: compareTo() and indexOf(); there’s no way to know which one to use. Thus the ambiguity would be overwhelming and, if that weren’t enough, the potential for runtime errors resulting from unintentional functional matches would be.

Of course Gosu can still use java.lang.Comparable, but since Gosu generics are covariant by default, we wouldn’t be able to properly support the type as needed, as with Collections#sort(). But what is Java really trying to accomplish with Comparable? Going back again to first principles, we could say it’s providing a way for a type to declare it implements the compareTo() method and a way for a consumer of that type to call the method in a type-safe manner. This is precisely what a Structural Type achieves.

So if we were to define Comparable in Gosu, we could use a generic structure:

structure Comparable<T> {

function compareTo( t: T ): int

}

But since we didn’t write the Java runtime library and since we want to remain 100% compatible with it we should keep using Java’s Comparable… or should we? Can the two types co-exist?

Above all, we must nominally implement Java’s Comparable in classes that intend to be Comparable, otherwise our classes won’t be recognizable as java.lang.Comparable in contexts that require it. What if our Comparable structure were to extend java.lang.Comparable?

structure Comparable<T> extends java.lang.Comparable<T> {

}

This accomplishes exactly what we’re after; we achieve contravariance and still remain compatible with Java’s Comparable. Basically we can replace usage of java.lang.Comparable with our own Comparable.

One other tidbit you may appreciate: Gosu infers the type arguments for structural types! This is a fairly new capability with the type system. Here’s a simple example:

var stuff: Stuff

var best = findBest( stuff ) // infers stuff as Bag<String>, then best as String!

function findBest<E>( bag: Bag<E> ): E {

...

}

structure Bag<T> {

function add( t: T )

function iterator() : Iterator<T>

}

interface Stuff {

function add( item: CharSequence )

function iterator() : Iterator<String>

}

Using a fairly complex algorithm the type system determines that in terms of Bag Stuff is structurally Bag<String>. This is how best’s type is inferred from the call to findBest(). Pretty cool, eh?

Back to Comparable, One thing should still bother you a little bit here. Although the Comparable structure enforces the compareTo() function name, it’s not as type-safe as it could be. Going back to first principals again, it’s better if Comparable were strictly a nominal interface. Although a Gosu class can still nominally implement our structure, if that’s its intention, we still leave open the case for using our structure… structurally, which is perhaps less type-safe than we’d like. Not a big deal, but it sure would be nice if we could somehow enforce contravariance without giving up nominal typing…

Earlier I mentioned Gosu generics are implicitly covariant by default. We have array-style covariance with generics for the same reason we don’t have wildcards – generics is hard; it’s an abstraction on top of an abstraction. Wildcards in particular is a major source of confusion with most Java programmers, including myself. Josh Bloch and others have written extensively on the subject, mostly about the pitfalls, the do’s and don’ts, and countless attempts at demystifying the matter. These works can be seen as a testament to its failure. Basically, users of a type shouldn’t have to deal much with the internal details of variance, it should be more straightforward than this, a lot more. This is why we went with array-style variance; it’s simple and intuitive and happens to behave as intended in all but rare situations. For instance, this assignment works as most people expect:

var list: List<Object> = new ArrayList<String>()

In Java this is illegal because without wildcards the type arguments are invariant. But the types are effectively assignable, so Gosu allows it, no wildcard monkey business. Yes, you could put a non-String in the list and then risk an exception at runtime, but in practice this almost never happens. So, to be frank, Gosu favors the relatively rare ClassCastException over crazyass wildcards no one really understands.

Sometimes, however, “almost never happens” isn’t quite good enough and we’d like to address that, but without use-site shenanigans. Basically we’d like to provide declaration-site variance similar to C# style in / out generics. But we still need to preserve our default behavior as array-style covariance, it remains the pragmatic way forward and sustains sanity when working with otherwise invariant Java libraries and such, not to mention it maintains backward compatibility. Is this possible? Can we have our cake and eat it too? I think we can…

Back to Comparable, here’s what we want:

interface Comparable<in T> {

function compareTo( t: T ): int

}

The in modifier on T declares T to be contravariant. C# in / out modifiers are aptly named because, as we discussed earlier, the general rule follows that a type variable passed in to an interface is contravariant, while one returned out of an interface is covariant. With this information Gosu’s compiler can verify all usage of T inside Comparable’s definition as well as usage of type arguments to Comparable, like with assignability checks and so forth. Here’s a doctored up example demonstrating some of the type system’s ability to enforce Comparable’s newly declared contravariance:

interface Comparable<in T> {

function compareTo( t: T ): int

function foo(): T // error: T used in an 'out' position

}

function testMe( text: Comparable<CharSequence> ) {

text.compareTo( "hello" ) // ok, since "hello" is a String, which is assignable *to* CharSequence

var works: Comparable<String> = text // ok, since CharSequence is assignable *from* String

var fails: Comparable<CharSequence> = works // error: String is not assignable from CharSequence

}

Nice. As the initializers for the works and fails variables indicate, Gosu upholds Comparable’s contravariant declaration, which is the opposite of what we’d get with default array-style covariance using java.lang.Comparable.

As satisfying as this may be, what about our default array-style covariance? How can these features co-exist? They have to cooperate otherwise a default generic type can compromise the type-safety of a generic type declaring variance with in / out. For instance, what about this scenario:

uses java.util.concurrent.Future

uses java.lang.Comparable

interface ThingBuilder<out T extends Thing> extends Comparable<T> {

function withName( name: String ): ThingBuilder<T>

function fromThings( things: List<T> )

function build( count: int ): List<T>

function build(): Future<T>

}

Builders produce things, which make them excellent candidates for covariant generics, so here ThingBuilder uses out to enforce that. But after careful examination, you can see that ThingBuilder breaks that contract. First, it extends java.lang.Comparable with T. Comparable is effectively contravariant with T, so this should be illegal, but since Java doesn’t have any way of declaring this, Gosu doesn’t know. Same for ThingBuilder’s usage of List<T>. List is effectively invariant with T because it uses T in both in and out positions in its definition. But, again, Java does’t let List tell us this. If we just let it go, ThingBuilder is no longer the sound generic type we declare it to be; it would compromise the type-safety we are trying to achieve.

One might assume we’ve run down a blind alley here. Not so fast. What if I told you Gosu can infer variance? It’s not that surprising really; if we can verify a type’s declared variance, we should be able to infer it, right? It’s a tough problem, but a totally manageable one. One we have cracked! I’ll save the details for a separate write-up, but suffice it to say you can include both Gosu and Java default generic types in the definition of explicit in/out ones. As such Gosu’s parser produces errors in all the right places in ThingBuilder:

uses java.util.concurrent.Future

uses java.lang.Comparable

interface ThingBuilder<out T extends Thing> extends Comparable<T> { // error: 'out' T used in an 'in' position with Comparable

function withName( name: String ): ThingBuilder<T>

function fromThings( things: List<T> ) // error: 'out' T used in an 'in/out' position with List

function build( count: int ): List<T> // error: 'out' T used in an 'in/out' position with List

function build(): Future<T>

}

Note, although Gosu does not allow wildcards, it takes them fully into account when inferring variance of generic Java types. So even this blatant attempt to throw Gosu off the scent doesn’t work:

public interface Comparator<T> {

int compare(T o1, T o2);

...

default <U extends Comparable<? super U>> Comparator<T> thenComparing(

Function<? super T, ? extends U> keyExtractor)

...

}

Although they bewilder programmers everywhere, Gosu has no problem deciphering wildcards to properly infer variance.

As we have this cake and eat it too, I want to stress that Gosu preserves the default array-style covariant behavior. The type system only infers variance where an explicit in/out generic class depends on the inference. All other usages maintain Gosu’s default behavior. Essentially, in/out style generics is a purely additive feature; all existing generic behavior is unaffected by it.

My goal here is to shed light on some of Gosu’s more esoteric, yet crucial type system features. First, I reviewed the fundamentals of function types, with a focus on structural assignment and variance, and how Gosu’s function types aim to simplify functional API design and usage by avoiding the intricacies of Java 8 Functional Interfaces and wildcards. Next I demonstrated how generic structures provide an extra level of type-safety to both simplify and seamlessly interoperate with generic types not under your control. Further, I explained the rationale behind array-style covariant generics and why we think this remains the pragmatic way forward. Finally, I introduced some powerful new capabilities with generic types, namely declaration-site generics and variance inference; With simple in / out declarations your generic classes are type-safe even while using generic Java classes with unspecified variance. Above all, I hope I’ve shown how all these features unite in the type system to make your experience with Gosu a pleasurable one.