Type parameters defined on Gosu generic types are reified, meaning their types are fully recoverable at runtime like other first-class types. Since the JVM does not support this feature, Gosu’s compiler is forced to implement it indirectly. This poses a performance problem I’ll address here along with a recent solution we’re currently experimenting with.

Generic type erasure has annoyed Java coders since generic types were introduced way back in Java 1.5. But a lot of guys claim type erasure isn’t that big a deal, which I generally agree with because most of the time we just don’t need to recover generic type information at runtime. Even so there are times when having it ranges from convenient to crucial. For instance, who here hasn’t written Java code like this only to be shamed by the compiler with “both methods have the same erasure”?

void addToGroup( List<Person> l );

void addToGroup( List<Group> l ); // error… both methods have the same erasure

Not the end of the world (I’m not a fan of overloading either), anyhow it’s a legitimate use-case closer to the “nice to have” end of the scale.

A similar situation arises with type checking against a generic type:

boolean isExclusiveToPersons( Collection<? extends Contact> group ) {

return group instanceof Collection<Person> ... // error… illegal generic type for instanceof

}

Again, not a crucial problem, but having it in this case improves performance; we must otherwise test the type of each element in the collection. Readability suffers too.

There are also times where we’d like to resolve a type argument directly at runtime:

class ArrayList<T> extends AbstractList<T> {

...

boolean contains( Object o ) {

if( o instanceof T ) { // error… Class or Array expected

...

}

return false;

}

}

This is another case that affects performance. Sure would be nice to have T here.

Similarly, we also encounter situations where we need to dynamically create a new instance in terms of the generic type:

return new T(); // error

return new T[]{t}; // error

This particular example may seem more indicative of a design flaw and that may be true at times, but there are common, real life use-cases that cry for this feature. To gain at least some modicum of appreciation for reification, especially as it relates to this example, you only need to experience the abomination that is Google’s TypeToken and the use-cases it attempts to remedy for the Gson and Guava libraries. This class is the preeminent poster child Kung Fu fighting for the abolition of type erasure. Well, after considering some of these examples or having used TypeToken we can probably all agree that a language with generics should at least provide a better runtime solution than erasure. Right?

Why doesn’t Java support reification? The Java designers claim, or at least used to claim, the primary reason for not supporting it is that it would break backward compatibility. Fair enough and regardless of whether or not that argument was ever valid, they probably are less inclined to fix it now. Fortunately, Gosu generics was designed atop a fresh language that, at the time, exclusively compiled from source at runtime, therefore there were no backward compatibility obstacles to contend with.

There’s another more critical issue to consider, however. Performance. Supporting reifcation isn’t free, in fact as you’ll see in a moment it can involve quite a bit of overhead. These days one of our primary goals for Gosu is to significantly improve runtime performance. To that end we are tuning the compiler to generate tight conventional bytecode where possible for all of Gosu’s language elements, we especially want to eliminate places where the compiler relies on expensive type system calls and legacy runtime artifacts. As you can imagine, this poses quite a challenge with respect to generic type reification since the JVM does not support it. But to fully understand why you’ll need to understand how Gosu currently goes about implementing type reification. It’s really not that complicated, there are basically three generic contexts that require type argument preservation:

For a class the compiler passes the type arguments into constructors as implicit parameters and then stores them in special fields corresponding with type variables on the class. For example, a hollow Foo<T> class looks something like this in its compiled form:

class Foo<T> {

private final typeparam$T: IType

construct(typeparam$T: IType) {

this.typeparam$T = typeparam$T

}

}

For a method the compiler simply passes the type arguments as implicit parameters and maintains them as locals:

static function singletonList<T>( t: T ): List<T> { ... }

// compiles to...

static function singletonList<T>( typeparam$T: IType, t: T ): List<T> { ... }

Similarly for an enhancement method the compiler passes all type arguments, both the method’s and the enhancement’s, as implicit parameters on the method and are maintained as locals:

enhancement IterableEnh<E> : Iterable<E> {

function each( operation(e: E) )...

}

// compiles to...

class IterableEnh {

static function each( $that: Iterable, typeparam$E: IType, operation: IFunction1 )...

}

That’s pretty much the essence of generic type argument preservation.

An alternative to preserving type arguments involves type specialization where basically the type system creates a completely separate type for each unique parameterization of a generic type. But that’s involved and still requires a bit of cooperation from the JVM, which it currently does not provide. But I digress.

So where exactly is the performance problem with Gosu reification? Can passing extra type arguments be all that expensive? Well, the cost isn’t so much in passing extra arguments as it is creating (or reifying) them at the call site. Before we get into the details I’d like to point out that of the three generic contexts enhancement methods are especially offensive with respect to performance degradation as it relates to reification. Consider the numerous and frequently used methods Gosu provides as enhancements to Iterable and Map. They all involve reification of the type parameters at the call site’s Iterable or Map. For example, the reification overhead involved with a simple access to the Map#Count property amounts to at least two TypeSystem#getXxx() calls, one for each type parameter on the call site’s Map (we’ll cover this process in detail next). While it’s great that Gosu can reify otherwise erased Java generic types while in the scope of an enhancement, the expense can be significant. Of course it all depends on the performance heat at the call site, most of the time it doesn’t matter, but when it does, it does.

Let’s consider a simple example with a basic generic class, say Foo<T>, to explain how the compiler reifies a type argument. Recall a generic constructor call site requires type arguments as implicit parameters to the constructor:

class Foo<T> {

construct() { ... }

}

new Foo<String>()

// compiles to...

new Foo( TypeSystem.get( String.class ) )

The compiler must reify the type argument for Foo<String> so that Foo’s constructor can preserve it in its typeparam$T field. The TypeSystem.getXxx() set of methods do most of the reification for us, for a price. This particular call to TypeSystem.get() is relatively cheap because the String class is a “frequently used” Java type and is directly accessible in our type system’s “special” cache, but it’s still not free and is more expensive than the new operation enclosing it. Other less frequently used classes are resolved by name and cost considerably more. For example:

new Foo<Bar>()

// compiles to...

new Foo( TypeSystem.getByFullName( "com.abc.Bar" ) )

getByFullName() is costly, it entails several method calls, hash lookups, and at least one string compare. Is there a better way? Why not store the type as a constant Class object? That way we could simply pass the class via a very fast LDC instruction. Well that works as long as there is a 1-1 correspondence between Gosu types and Java classes, which is not the case. Gosu’s type system supports features Java’s doesn’t e.g., function types, compound types, custom types, etc. But even a simple parameterized type can’t be preserved as a Class reference. Take the following example:

new Foo<List<String>>()

// compiles to...

new Foo( TypeSystem.get( List.class ).getParameterizedType( TypeSystem.get( String.class ) ) )

We simply can’t represent List<String> as a Java Class constant, so we still have to generate code to reify the type in a form the type system can digest. And as you can imagine this particular form of parametric reification comes at a hefty price. It seems we are at an impasse…

What’s really frustrating about all of this is that most of the time type arguments aren’t used at runtime. As such the work involved in creating them is largely superfluous because our code rarely cares about them. But maybe this is a blessing in disguise… When we need them they have to be there, otherwise why blow up performance reifying them if we don’t have to? We really only need to preserve type arguments so they are recoverable if they are needed. So why not support reification lazily such that type variables resolve on demand only when they are needed? Instead of storing a type variable’s value directly as an IType, we can store it indirectly through a lazy IType:

public class LazyTypeResolver extends LocklessLazyVar<IType> {

public interface ITypeResolver {

IType resolve();

}

private final ITypeResolver _resolver;

public LazyTypeResolver( ITypeResolver resolver ) {

_resolver = resolver;

}

LazyTypeResolver() {

_resolver = null;

}

@Override

protected IType init() {

return _resolver.resolve();

}

}

LazyTypeResolver extends a typical lazy access implementation. Basically, LocklessLazyVar provides a get() method to lazily initialize our IType via a call to our init() implementation, which calls through to the ITypeResolver functional interface the first time get() is called. With the LazyTypeResolver in hand we can pass along type arguments much more efficiently because we simply avoid the comparatively expensive reification.

Revising our simple Foo<T> bytecode we have the following.

class Foo<T> {

private final typeparam$T: LazyTypeResolver

construct(typeparam$T: LazyTypeResolver) {

this.typeparam$T = typeparam$T

}

}

Basically, anywhere the compiler previously used IType to store, pass, or receive type arguments, it now uses LazyTypeResolver. After making these changes our first order of business is to make the “frequently used” types as fast as possible. We do that with the following subclass:

public class ClassLazyTypeResolver extends LazyTypeResolver {

// Predefined resolvers for frequently used classes

public static final ClassLazyTypeResolver Object = new ClassLazyTypeResolver( Object.class );

public static final ClassLazyTypeResolver String = new ClassLazyTypeResolver( String.class );

... // many more

private final Class _class;

public ClassLazyTypeResolver( Class type ) {

_class = type;

}

@Override

protected IType init() {

return TypeSystem.get( _class );

}

public static java.lang.String getCachedFieldName( Class cls ) {

String fieldName = cls.getSimpleName();

try {

for( Field f: ClassLazyTypeResolver.class.getDeclaredFields() ) {

if( f.getName().equals( fieldName ) && ((ClassLazyTypeResolver)f.get( null ))._class == cls ) {

return fieldName;

}

}

return null;

}

catch( IllegalAccessException e ) {

throw new RuntimeException( e );

}

}

}

This class not only provides an efficient way to resolve Class-based types, it also provides a predefined set of resolvers for frequently used types, which translates to a lightening fast GetStatic bytecode instruction for a type argument:

new Foo<String>()

// compiles to...

new Foo( ClassLazyTypeResover.String )

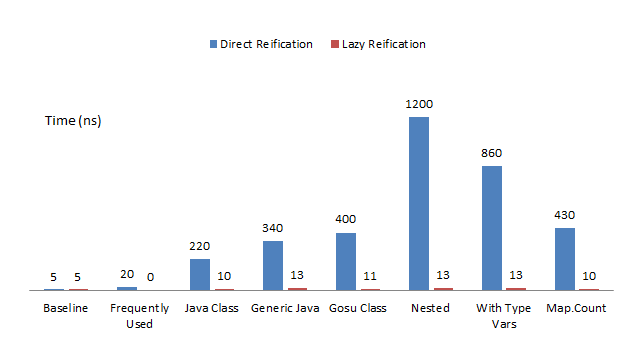

That’s a huge performance gain right there. (Micro benchmarks comparing direct and indirect reification appear later in this document)

Otherwise, if the Class is not a frequently used one, we generate a constructor call, which is still quite fast:

new Foo<Bar>()

// compiles to...

new Foo( new ClassLazyTypeResolver( Bar.class ) )

But what about a more complicated use-case, like one involving a type variable as a type parameter:

class Thing<T> {

function mapThings<E>( name: String, E... ): Map<String, List<Thing<E>> {

var map = new MyMap<String, List<Thing<E>>>()

...

return map

}

}

The constructor call to MyMap involves type variables as type parameters; their types are not known at compile-time, therefore the compiler can’t directly reify a type with one of them as a type parameter e.g., Thing<E>. What to do?

Without LazyTypeResolver the compiler generates code to reify the type directly like this:

var map = new MyMap( TypeSystem.get( String.class ),

TypeSystem.getByFullName( "java.util.List" )

.getParameterizedType( TypeSystem.getByFullName( "abc.Thing" )

.getParameterizedType( typeparam$E.get() ) ) )

The compiler knows how to resolve any given type variable, it is either a field on an enclosing class or it is a parameter on an enclosing method. In this case since E is a type variable on a generic method directly enclosing the new expression, it is a simple local variable access. It gets a little hairy with anonymous classes and closures, but it’s always a field somewhere up the inner class nest or a local.

One idea is to have the compiler create an anonymous class implementing ITypeResolver for us and then generate the reified type variables inside its resolve() method:

var map = new MyMap( TypeSystem.get( String.class ),

new LazyTypeResolver(

new ITypeResolver() {

override function resolve(): IType {

return TypeSystem.getByFullName( "java.util.List" )

.getParameterizedType( TypeSystem.getByFullName( "abc.Thing" )

.getParameterizedType( typeparam$E.get() ) ) )

} ) )

This could work, but places a lot of burden on the compiler to generate anonymous class artifacts outside the scope of the current compilation unit. It’s doable, but not optimal in terms of the compiler’s current design and, worse, would break at least one use-case involving GUnit testing where synthetic anonymous classes such as this one aren’t persisted to disk in a normal build cycle. We’d have to find a way to make the anonymous class not quite anonymous and dynamically loadable by name with some naming convention mixed with a thread-local cache or some such – again, not optimal.

It would be cool if the JVM could help us make that anonymous call dynamically. What we’d need is to capture the body of the resolve() method somehow and invoke it as if it were a ITypeResolver instance. Essentially:

var map = new MyMap( TypeSystem.get( String.class ),

new LazyTypeResolver(

\-> TypeSystem.getByFullName( "java.util.List" )

.getParameterizedType( TypeSystem.getByFullName( "abc.Thing" )

.getParameterizedType( typeparam$E.get() ) ) ) )

If we instead capture the reification code in a synthetic method, we could use the JVM’s newish InvokeDynamic instruction to treat it as a functional call:

var map = new MyMap( TypeSystem.get( String.class), new LazyTypeResolver( \-> lazytype$0( typeparam$E ) ) )

...

private static synthetic function lazytype$0( typeparam$E: LazyTypeResolver ): IType {

return TypeSystem.getByFullName( "java.util.List" )

.getParameterizedType( TypeSystem.getByFullName( "abc.Thing" )

.getParameterizedType( typeparam$E.get() ) )

}

Generating a lazytype$ method is a simple matter of determining which, if any, type variables need to be captured as method parameters and knowing if the method should be static or not. Otherwise, the compiler’s existing reification bytecode generation will work as the body of the method just as if it were part of the original one; field references are in the same context because the method is generated as a sibling method of the one in context.

The InvokeDynamic call we use leverages the new LambdaMetafactory#metafactory() utility to basically wrap a functional interface call to ITypeResolver.resolve() as a static or virtual call to a lazytype$ method. The following snippet summarizes how we generate the InvokeDynamic call using ASM. You don’t really need to understand ASM so much to understand what’s going on, but reading up on MethodHandles and LambdaMetafactory is probably worthwhile.

MethodType mt = MethodType.methodType( CallSite.class,MethodHandles.Lookup.class, String.class, MethodType.class,

MethodType.class, MethodHandle.class, MethodType.class );

Handle bootstrap = new Handle( Opcodes.H_INVOKESTATIC, LambdaMetafactory.class.getName().replace( '.', '/' ),

"metafactory", mt.toMethodDescriptorString() );

Type resolveDesc = Type.getType( LazyTypeResolver.ITypeResolver.class.getDeclaredMethod( "resolve" ) );

methodVisitor.visitInvokeDynamicInsn( "resolve",

Type.getMethodDescriptor( Type.getType( LazyTypeResolver.ITypeResolver.class ),

getAnonCtorParams( expression ) ),

bootstrap,

resolveDesc,

new Handle( Opcodes.H_INVOKESTATIC,

"abc/Thing",

"lazytype$0",

"(Lgw/lang/reflect/LazyTypeResolver;)Lgw/lang/reflect/IType;" ),

resolveDesc );

This should look familiar If you’ve examined the bytecode the Java 8 compiler generates for Lambda expressions. This is pretty much exactly how javac compiles a lambda, which inside the JVM is always an anonymous wrapper implementing a functional interface. Read more about lambdas and functional interfaces as they relate to Gosu’s Java 8 support in a future post.

So where do we stand? Do LazyTypeResolvers significantly improve Gosu’s reification performance? If anyone is still following along, here’s the money shot:

As you can see our lazy strategy outperforms direct reification by a factor of 20 to 200 and beyond, depending on the complexity of the types to reify. As I mentioned earlier one of the more problematic use-cases involves enhancement features on commonly used generic types such as Iterable, Map, and the like. The last benchmark in the graph exercises this use-case against the everyday Map.Count property. We’re especially encouraged by the results showing a 40X+ performance gain, this takes a ton of pressure off enhancement usage. Moreover, the lazy approach has reduced the pressure across the board to the point where reification overhead is no longer a concern. Is the overhead completely gone? No. We still require an extra reference per Class type variable as a synthetic field (the typeparam$ fields), there’s also a bit of extra memory involved with lazy wrappers, and the tiny bit of indirection involved with the get() call to reify types. But, as the benchmarks clearly demonstrate, this amounts to nothing more than low-grade noise in the grand scheme.

This change coupled with the more general effort to optimize the Gosu compiler in terms of unnecessary type system access and legacy runtime calls considerably reduces the runtime burden of the type system. In fact with the exception of reflective use-cases and custom types, which are features afforded by the type system, the overall impact on runtime performance in most cases approaches zero. It’s still not zero though; we have plenty of work ahead of us regarding compiler optimizations and such. All the same we are satisfied with these results.